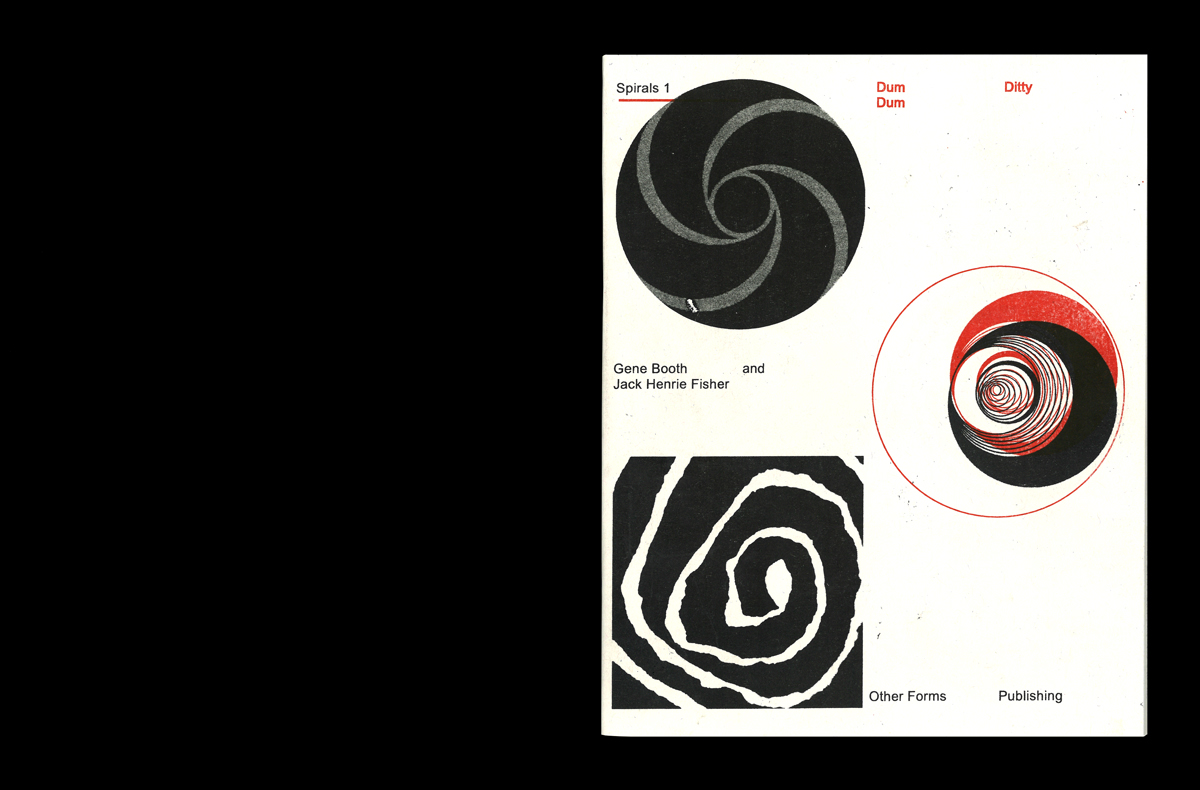

Spiral Concept

Our concept of the spiral in recorded music is that it is a literal diagram of the material medium of the vinyl record. Theodore Adorno writes that music literally becomes writing with the invention of the phonograph record: this writing is inscribed as a spiral on the vinyl platter. The spiral inscription on a shellac disc or whatever the material happens to be, literally is writing. It follows (like a curve unfolding from a central point) that the seemingly decorative appearance of spirals on album cover art, or spinning as record label logos, or in lyrics (and also in musical structures like Coltrane solos) is a figure (an illustration but not only that; it is also the internal diagram) of that musical material medium-machine that is the vinyl record (and maybe the cd?). This is what is so intense and fascinating about the spiral form when one starts to think about it and see its multi-dimensional instances in the commodity world of recorded music.

The visual figure of the spiral in phonograph music, initially shaped by the material spiral structure of the phonograph record, is so forceful (as forces of production are) that it projects itself into the world (pops up, emerges, comes to the surface, SPIRAL-LIKE) through graphic forms like record covers and record company logos, AND AND AND the collective social forms that produce and consume (jazz, rock/pop, rap) music in the first place. Spirals in this sense are inorganic machine traces that unconsciously recur as the material dream sequence of the mechanical apparatus of the record player in capitalism. The black fan Atlantic logo really nails it. But yeah one can, as Freud describes in dream interpretation, resist and repress traumatic truths by misreading the spiral figure as something natural or organic (like a nautilus shell or soap bubble). But the mechanical spiral nevertheless pushes out and is formalized through dreams and slips of tongue and mishaps with various objects.

The phonograph record not only encodes writing in its material medium as a spiral, but also, precisely by means of this inscription — somehow — becomes the fundamental modular form in which the social relations of (music) production are captured and reproduced as a commodity: “the two-dimensional model of a reality that can be multiplied without limit,” as Adorno writes. This is what is so utterly hypnotizing and agonizing about the phonograph record for the modern listener and record buyer (not to mention music critic) throughout its history, including, especially, the present extremely late moment of its reemergence.

The notational system for music prior to the invention of the gramophone, Adorno writes, was an arbitrary signifying system, a structured collection of “mere signs.” Any notation “#” could mean whatever sound #, in precisely the sense that every relation between a signifier and a signified, as people were always pointing out in the twentieth century, is arbitrary. Through the gramophone, however, music liberates itself from the contingent shackles of such notation, from its long subordination to the dictates of marks on paper, and itself becomes writing. The phonographic spiral can be “recognized as true language to the extent that it relinquishes its being as a mere sign: inseparably committed to the sound that inhabits this and no other acoustic groove.” This remains true and becomes more true at the historical moment when the DJ starts “scratching” the record by moving it back and forth beneath the stylus to make another kind of sound.

Editorial note: A spiral is “a curve which emanates from a point, moving farther away as it revolves around the point,” going neither up nor down (says Wikipedia). That’s the formal idea of the writing in volume 1 of this zine/pamphlet/treatise: we move ever further (farther?) afield in each editorial “rotation,” each variable set of paragraphs (conveniently arranged under identifiable subheadings) follows from the previous one but while changing or expanding its course, all the while centered around a single point: the rock or jazz spiral that is the spiral of commodity circulation in capitalism.

Atlantic Logo

The pinwheel or black fan Atlantic logo is a perfect optical machine of a logo, a lucid motor of mechanized abstraction. As the turntable revolves, the logo is animated to become no longer simply a sign or a mark, but a compressed structural diagram of the very inorganic logic of the phonograph itself — a twisting spiral drawn by the turntable, spinning endlessly into the black void of the vinyl platter. This hypnotic Atlantic inscription debuted in the so-called bullseye position, the center of the record, in 1958 — Charles Mingus’ Blues and Roots — and only lasted for two years, after which the black fan figure was displaced from its position of mesmerizing power at the label’s center, and became statically enframed in a rectangle, decentered beside the letter “A” and the name “Atlantic,” in a composition which has remained until today, stamping everything from Voulez Vous to Lil Uzi Vert.

John Coltrane’s Giant Steps, his first Atlantic record and one of the first Atlantic records emblazoned with the (plum orange) bullseye spiral, includes, as the last song on the first side, the song “Spiral.” See what we’re talking about? This is an album on which Coltrane begins to compose his own songs, and begins to compose the sort of songs that are constructed by solos, liquidating chords and modes, and stacking them vertically in accelerating, twisting sheets. Jazz writers go on and on about this. Spirals and writing (writing here in the sense of musical composition, which is admittedly paradoxical to the degree that the music is improvisational) thus begin together in a remarkable coincidence. This is one example of how the material spiral of the vinyl medium conditions the quality of the music it inscribes. Giant Steps is a blistering leap in the direction of music made for, and under the sign of, the material and mechanical phonographic spiral. Adorno lamented that there was no such phonograph-specific music, in 1934, before the release of Giant Steps. Yeah yeah yeah Adorno hated jazz. But the very signature sound, on the “Spiral” cut, takes the audio shape of the material medium on which it is etched. Can you hear it? It’s almost unbelievable. Nat Hentoff, in the writing on the back of Giant Steps (Atlantic SD-1311), characterizes Coltrane’s spiral signature sound as animated by “the fury of the search.”

The circle-and-crescents spiral of the “black fan” is equal parts phono-spiral and globo-sphere. Removed from the bullseye, the company “crossed the Atlantic” in 1966, signing a reciprocal deal with England’s Polydor Records. This effectively signaled the beginning of an expansion (in the familiar manner of globalizing capital) in the label’s focus from American regionalism (mainly New York and Memphis) to London, and then to world markets beyond. This move coincided with a shift in genre-focus away from soul to rock, starting with The Cream (who, like creamer, literally whitened the label’s once Black “coffee”). The hole in the middle therefore reads as an assertion that Atlantic, the American music corporation, was the center of an expanding world-system. It also looks like a fan, or a pinwheel; definitely wind-involved, suggesting energy radiating out, like the label’s reach, as opposed to inwards, like how a record materially and mechanically sucks a stylus in. The smooth, static, and infinite interiorization of the phonographic spiral meets the full-of-social-friction but smoothly-imagined expansion of capital, an American invasion in the opposite direction.

Capitol

Speaking of capital, Capitol Records started in 1942, the first big record label in California. In ‘61 they adopted the iconic orange-yellow swirl for their singles, twelve years after the 7-inch format was introduced. At this time the roster consisted of novelty acts, “dumb” teenyboppers, bands like The Kingston Trio, the whitebread pap typical of the Elvis-to-British Invasion chasm that forms chapter one in your typical rock history. But surf hit from the Pacific Ocean while the British Invasion hit from across the Atlantic a year later. Capitol landed the Beach Boys and the Beatles, and consequently, when people who were buying those singles in the 60s think of these bands, they think of that candy-corn-colored spiral, etched (softly burned) into their imaginary optical nerves.

The other significant design element on the Capitol single label is the label name, written in a stylized cursive, beneath a capitol dome — it’s obviously supposed to be the US capitol in DC, but 50’s-era Capitol exec Don Hassler swears the dome and the name were meant to represent Hollywood, “considered the entertainment capitol [sic] of the world” (emphasis added) — and four stars. Why a national signifier, as opposed to showing, say, the Capitol Records building in Hollywood, a modernist architectural landmark with a spiral structure that was built only 6 years before the single label was first used? Record company capital in this case borrows the image of the state in order to convey its authority in the same way that capital writ large, even (or especially) in its transnational globalizing tendency, requires the police power of the nation-state for its violent dominion over all social life. The sign of the capitol in the Capitol label clearly attempted to confer the authority of the US nation-state onto the music. It said this is American rock and roll (even when it is the Beatles). This implication became ironic when Capitol was bought in ‘55 by UK powerhouse EMI, the first instance of the weird and ongoing back-and-forth between England and the States that is the label’s between-the-lines corporate history. This system of culture swiping reminds us of the origins of the history of rock and its theft of black musical forms. The Beatles steal ideas from Elvis (the original white rock colonizer figure) who originally stole it from black music; The Byrds et al steal ideas from The Beatles et al who then steal ideas from Dylan who The Byrds also stole from and on and on. Furthermore, Capitol takes the English Beatles and reshuffles their identity for American access through track reorganization on LPs and different sleeves. Back, or even back-and-forth once is one thing, but this constant criss-crossing flow of sounds, money, and images/identities in the production of nationalist phonographic commodities constitutes a primary oscillation, which time amplifies into a historical spiral as rock keeps getting bigger.

The label’s shockingly banal brightness emblematizes the explosion of color that the new rock brought to music and its consumers. But this emerging spiral empire of rock forced other spirals into contraction: Merle Haggard hit in ‘68 with “Mama Tried,” but says that behind the scenes, “Capitol were also disappointed in everything but the Beatles. There was nothing in the world selling except Beatle music. Every country act in the entire fucking world had just got fired. And it just so happened that during that really strange Beatlemania I got a goddamn hit.” This anomaly is not a miracle; it speaks to the dialectical character of spirals as well as to the power of Haggard’s 60’s mid-career hit singles (not just “Mama” but also “Fighting Side of Me” and “Okie From Muskogee”). Because the line etched by the spiral also creates a negative space running alongside it, a frontage road that parallels the highway. All spirals have this little black void running beside its shining white line. And it is in this void that “Mama” appeared. Also, Mama is actually really different from most Haggard songs; it is tighter, and has a bell-like guitar for a hook that, while not Beatleseque, is definitely more pop than typical Haggard works like “Green, Green Grass of Home.”

Some Jazz Spirals

Ok now we’re gonna look at several examples of jazz spirals, using the song title “Spiral” as a starting point, and consider both musical and social permutations. It should be noted that we are limiting ourselves here to songs in jazz simply called “Spiral” — omitting Coltrane’s song “Spiral,” which is discussed above. The Crusaders song called “Spiral” is omitted because it is post-Jazz Crusaders, and could therefore be considered to be fusion or R’n’B music. Similarly, the Herbie Hancock song “Spiraling Prisms” is omitted because of the additive prisms, which demands a further, separate categorization.

Bobby Hutcherson’s Spiral LP was first released in 1979, with a pattern that suggests a particular fragment of a spiral on the cover. The music was recorded at a session in 1969, save for one outtake song from the 1965 Dialogue session. Spiral can be seen as part of a greater spiral of collaboration involving multiple recording sessions, done mostly (though not exclusively) for Blue Note, between 1963 and 1970, involving one or more members of the Spiral band: drummer Joe Chambers, bassist Reggie Johnson, pianist Stanley Cowell, tenor sax player Harold Land, and Bobby Hutcherson on vibraphone. The most prolific cohorts on this team were Hutcherson and Chambers, who played together on two sessions for Archie Shepp, one for Andrew Hill, and nine for Hutcherson. Over the course of the Hutcherson-Chambers collab, Hutcherson recorded 16 Joe Chambers compositions; the title track of Spiral itself is a Chambers credit. During this time, both players had played many other sessions as well, with some other of the heavy New Thing players around (in addition to themselves): Herbie Hancock, Joe Henderson, Freddie Hubbard, Grachan Moncur III, Sam Rivers, Wayne Shorter, Sonny Simmons, Charles Tolliver, and Tony Williams, to name a mere few. Around the time of the Spiral session, Hutcherson was also collaborating regularly with pianist Stanley Cowell; Spiral was the second of four sessions they would have in ’68 and ’69. Spiral was also the second record in Hutcherson’s collaboration with Harold Land, which lasted until 1971, and produced ten albums overall.

This is stated not simply to note a set of concentric circles and phases of overlap in these individuals’ careers, but also to imply that musically, the players were comfortable with each other, and the relatively new style in which they were endeavoring to play. Everyone sounds very pleasantly together; on the title track, their emulation of the titular word takes some time to develop, as Hutcherson builds his phrases from hiccuping short phrases before breaking into longer lines which create a cascading feel. Following a drum break, both Land and Cowell repeat this motif in short solos, which leads to passages more choppy than spiraling. The band sounds more developed on the session from the following year that eventually became Medina. If you are at all like me, you may spend too much of your jazz listening time waiting for the sax to come in; what makes the band here so fun is the productive concision with which Hutcherson, Cowell, and Chambers play together, acting as extensions of each other while making definitive individual statements. This isn’t to imply that Land doesn’t contribute with an equally comradely feel, but simply that the work of those three players locks together with an instinctive quality that is all encompassing, providing as well a drive for the group to extend their reach, hard-bopping toward spiritual jazz pastures.

Spiral is a part of a separate contextual spiral to be considered here: Blue Note sessions of the 1960s not released until the mid-70s or later. Spiral and Medina were recorded in ’68 and ’69; they were released respectively in 1979 and ’80. This spiral includes sessions by Chick Corea, Booker Ervin, Grant Green, Andrew Hill, Elvin Jones, Freddie Hubbard, Jackie McLean, Lee Morgan, Sam Rivers, McCoy Tyner, and Larry Young, among others. Many of the records have been repackaged multiple times in the time since their eventual release, most recently with artwork that references the classic 1960s Blue Note look. In 1998, Medina was issued in a CD package with Spiral; this allows the output of this band to be heard in its entirety, with both sessions plus the one outtake from Dialogue.

Interestingly, pianist Andrew Hill, who, as it has been previously noted, played with Bobby Hutcherson (and vice-versa) earlier in their careers, recorded a song called “Spiral” on an album of the same name that was released in 1975, four years prior to the belated issue of Hutcherson’s 1968 “Spiral” session. It features a song called “Lavergne,” which is titled after Andrew Hill’s wife, which is something that Sam Rivers did as well, naming a song “Beatrice” in tribute to his wife (and later titling his record label Rivbea, combining his last name and her first). Additionally, McCoy Tyner recorded a song and album called “Song for My Lady” — so as you can see, this is another spiral to be followed through upon. Returning to Andrew Hill’s “Spiral,” the band accompanying him on this track includes saxist Lee Konitz, trumpeter Ted Curson, bassist Cecil McBee, and drummer Art Lewis. Konitz was the old man of the group; in the spring of 1949, as a young player, he had participated in recording sessions with Lennie Tristano that produced “Wow”, “Crosscurrent”, “Intuition” and “Digression”, with drummer Harold Granowsky, bassist Arnold Fishkin, pianist Tristano, guitarist Billy Bauer, and fellow sax player Warne Marsh. The music they made is relevant to mention here for two reasons: first, Tristano’s writing, which, with contrapuntal harmonies and rhythmic displacements, suggested at that time a new direction in post-bop, combining rhythmic coolness and spiky harmonic frontline aggressions with melody lines in “Wow” and “Crosscurrents” that spiral madly in the hands of all the soloists (but never more so than when the two saxes play together on the heads of each song). Secondly, Tristano had called for performances of several pieces of free improvisation to be recorded as well, an idea so radical that he later stated, “… the engineer threw up his hands and left his machine. The A&R man and management thought I was such an idiot that they refused to pay me for the sides and to release them.” Further, the men in control of the session erased two pieces that they deemed a waste of tape, and the two surviving pieces were subsequently shelved by Capitol until copies played on Symphony Sid’s radio programs created a demand. While these pieces are pioneer takes at free jazz, it can be argued that within the collective improvisation of the 1920s there is an even earlier form of the same (admittedly, with set key and chord changes). As the players disperse riffs in response to other riffs, there are plenty of mini-spirals in “Intuition” and “Digression,” and some un-spiraling as well, which is to be expected in a performance with no established key, melody, time signature, or rhythm, using only a sequence and approximate timing for each player’s entry, alongside their practice of “contrapuntal interaction.” Again, this is mentioned because 25 years later, Lee Konitz played on an Andrew Hill session that produced a song called “Spiral.” Hill’s music had proven to be almost limitlessly expansive in its pursuit of alternative phrasing and dissonance, rooted in melodic blues and European voicings. For this per-formance, there are times where the three principle components of the bands — rhythm, piano, and frontline — all seem to be playing in different time signatures, each moving together in their own spirals that interlock to provide a full performance.

The cover of Andrew Hill’s Spiral LP, however, makes no visual reference to its namesake.

Vertigo

Linda Nicol designed the so-called “swirl” logo for the English prog label Vertigo, a subsidiary of Philips, in 1969. The Vertigo swirl complicates and supercharges the spiral form, feeds it LSD, and sets it loose. It appeared on Vertigo lps from 69 to 73 at which point the logo was lamely redesigned by Roger Dean. Dean’s fantastical pseudo organic spaceship design, as in his work for Yes, Osibisa, and others, implies a lowest-common-denominator progressiveness that invokes the retrogression of fantasy worlds and mostly ignores the radical geometric implication of the Nicol swirl.

Vertigo Records boss Olav Wyper’s remembers the origin of the logo: “I wanted something that was very visual. You have this large space on a twelve-inch record that really doesn’t do anything. I have always been a very visual person. When I worked in advertising that was one of my strengths. I wanted the label in the center of the album to be very visual. One thought I had — make it spell something only after the record is turning at speed — was something we tried to do without success.”

How could this visual concept have worked? Could a letterform be “drawn” through a circular rotation of its component parts? We have tried to imagine this possibility of letters coming into animated appearance through iterated rotation and have concluded that it isn’t possible in a world like ours governed by both the laws of two-dimensional optical form and basic typography. This leads us to the conclusion that language, at least understood in its western forms as a variable concatenation of roman alpha numeric glyphs, is not possible within the form of a spiral, at least in the way visualized above.

The spiral form excludes language because the form of the phonographic spiral is its own language, a purified language inscribed in the material substance of the record, as Adorno writes in the “The Form of the Phonograph Record,” in which sign and meaning are grounded together in an immediate presence, abolishing the everyday distance and deferrals of linguistic meaning. We’ll return to this later but here’s what Adorno says (which we already quoted, coming back again, but wider this time): “If, however, notes were still the mere signs for music, then, through the curves of the needle on the phonograph record, music approaches decisely its true character as writing. Decisively, because this writing can be recognized as true language to the extent that it relinquishes its being as mere signs; inseparably committed to the sound that inhabits this and no other acoustic groove.”

The Vertigo boss continues the revery of his corporate logo: “I was sitting in traffic, it was raining; my car windows were steamy and I wanted to look at something in a shop window across the street. I drew an increasingly large circle, like a spiral, in the fog of the auto glass.” Ok whatever. He goes on: “I wanted something on the A-side of a record that drew you in. So that when the record spun you felt as if everything was pulling you towards the record. I did the rough designs, and then a lady — Maggie — in our art department came up with the final version. What we did was use this to take up the whole of the label on the first side of a record, so it really stood out.”

Maybe Maggie knew about the rotoreliefs of Marcel Duchamp, because they look very similar to the Vertigo logo. Duchamp, a self-identified “precision oculist,” set up a booth in 1935 at the Concours Lépine inventor’s fair in France, exhibiting what he called optical phonograph records, shellac plates which would spin on vertically-mounted turntables. The rotating discs produced no sound but, instead, optical events as they spun. They came in sets of six. As they spun, each produced, as Rosalind Krause writes, “an unstable kind of volume, appearing at certain moments to project forward but at others to recede, setting up the feeling of a thrusting motion.” Each disc produced different palpably abstract scenes of 3D metamorphosis, continuously mutating from something to something else and back again while repetitively evoking the abstraction of depth. While these demonstrations were, on the one hand, meant to simply produce “optical pleasure,” they went further, in the reflexive sense that they produced not only a “visual” to be observed but, as Rosalind Krause explains, the specific visual of an eye (of ocular organs as flower parts) which looks back at the viewer, returning her own bewildered or enlightened (i.e. stoned) gaze.

The optical event which these two-dimensional compositions provoke in the viewer, as she sees and is seen by them, and grasps their totality as compositions, demonstrates what Rosalind Krause calls the “logical moment” in visuality. The logical moment in the case of Vertigo/Duchamp is produced by a three-dimensional volume that “doesn’t violate the two-dimensional integrity of the picture plane.” A three dimensionality that is not an illustration in perspectival space. This logical moment in which the third dimension is non-figuratively (i. abstractly) apprehended is produced in the “stark clarity of a demonstration of the inner workings of the law” of cognition that is at work in this perception of three dimensions in two. It is the magic trick of reason, an intellectual perception, which happens in the eye/brain of the viewer, not in the thing itself. Duchamp was really into this.

We can imagine the pleasurable experience of this logical moment unfolding within the contours of the enlightenment scene of detached thought, one in which the bourgeois subject calmly surveys an inner scene, perhaps while reclining in an Eames lounge chair and illuminated by suspended Noguchi paper lanterns, alongside an unspeakably warm sounding single-ended vacuum tube amplifier. Or maybe it’s a dog in front of a Victrola. But the pleasure in this scene is complicated. The apprehension of the “languidly unreeling pulsation,” of Duchamp’s precision optics (and its exact repetition in the Vertigo record label) is structured by a split or repression, says Rosalind Krause. It is therefore unconscious. The spiral discs, as they promiscuously solicit visual attention, create a momentary vector of resistance to the rationalization of Cartesian space, a momentary opening for the irruption of an optical unconscious. A space for the appearance of the spiral. The logic of this moment indicates that what we are discussing is in fact a disenchantment, rather than a simple hypnosis.

On the early Vertigo releases, this spiral logo appears in large format on the A side label, composing, like the Atlantic bullseye, a figure that hypnotically loops with the rotations of the turntable. The record thus becomes a multi-media object, a medium of sound but also of “visuals,” an eye candy machine for the acid folks and tripping hippies, a mini-movie to trip out on in the fixed abode of your bedroom or wherever in the house the stereo is positioned and plugged into the wall. Vertigo is the spatial disorder (a vertical version of Rimbaud’s “systematic disorganization of the senses”) that is produced in the private bourgeois hippie interior. A yawning chasm, an abundance of depth, a breast, a phallus, something, magically appears within the confines of the tripping teenager’s bedroom. Or, in a major plot twist, could it actually be a communist party space we’re talking about at this point?

In any case, the phonograph record opens space, as the name Vertigo acknowledges. Adorno characterizes the limits of this phonographic space as a bad trip: “here too a pure identity reigns between the form of the record disc and that of the world in which it plays: the hours of domestic existence that while themselves away along with the record are too sparse for the first movement of the Eroica to be allowed to unfold without interruption. Dances composed of dull repetitions are more congenial to these hours. One can turn them off at any point.” But we don’t have to be so negative.

The domestic interior, the teenager’s bedroom or the listening room of the pipe-and-slippers crowd, is a space for the bourgeois subject to impregnate himself against the precarity and the monotonous threat of modern industrial life. This interior provides the illusion of “personality” against the anonymity of urban life for its inhabitant. The phonograph player was an essential component in the construction of this domestic space of leisure and recreation and undifferentiated individuality, bringing the formerly public and collective life-world of music into the private space of the bourgeois interior. But the phonographic apparatus as a commodity has, like everything else in capitalism, scalar levels of value: from ultra luxury analog “warmth” for those who can buy it to mass-produced free cold digital-streaming crack for everybody else.

But there is a countervailing, communist idea of the space of the phonograph, one that is crystallized in the image called Co-op Interior, produced in 1926 by Hannes Meyer, the director of the Dessau Bauhaus. Architectural critic Pier Vittorio Aureli writes that the Co-op Interiur, “as one of the most radical images of the uprootedness and ephemerality of modern living, challenges the most enduring condition in which human dwelling has taken place: that is, the condition of private property in the form of the estate.” Property as real estate is one thing that compels the reproduction of capitalism. When you own a house, you need the police force of the state to secure it against the population without property. And of course you need the state in the first place to help seize the land from whomever was living there before. It is cool that in the Hannes Meyer image, a phonograph player, that cultural commodity seemingly born as a bourgeois luxury utensil, appears as a crucial element, along with a bed, table, and shelf, in the minimal image of communist life.

Back to Vertigo. Like the Atlantic pinwheel, the Vertigo swirl is not a “pure” spiral. But it solves the spiral’s formal puzzle problem in the opposite way: while the Atlantic pinwheel reduces the spiral form to ultra-2D, the Vertigo swirl postulates, in the manner we have noted, the third dimension. It adds a spheroid aspect to the spiral by conflating three different spirals within a 2D circle. It is more visually complex than the flat spiral that is, for instance, inscribed on the vinyl platter. But the source of this complexity — its implication of 3D — is at the level of opticality only: it is an illusion. But it is an illusion that awakens the mind, the unconscious.

Vertigo: a spiral in a spiral in a spiral. Incredibly suggestive, beyond the up/down optical illusion. I count three possible objects it can take the shape of, but maybe there’s more. The black center bounded by arcs evokes a monstrous droopy eye, or a cannon tube or glottis. It makes it seem suddenly that all 2D spirals everywhere are always meant to imply the 3D one. This is a super spiral, befitting the label that would eventually release “Supernaut” onto the world. This is the spiral that most directly emblematizes hypnosis, or at least dizziness and its induction, if the label name and logo are to be taken as literal analogues. But, as we have noted in Duchamp’s rotoreliefs, the Vertigo super spiral goes beyond elementary punchline hypnosis, as it makes visible its own conditions of visual possibility: the spiral opens the mind and makes it knowable and therefore disenchants the visual world that is otherwise filled with fake spirals like the one Roger Dean drew.

Vertigo was a major home for prog rock in the 70s (but not so monotonously: its progrock spectrum moves from psych-folkies Cressida and Fairfield Parlour, through the exotics and eclecticism of Gentle Giant and Jade Warrior, to dis-appear into the ritual blue collar heaviness of Patto and Black Sabbath). Now, the Vertigo label was meant to invoke a hypnotic state when its records were spun. But is hypnosis the state or power that Vertigo’s prog bands were actually aiming for, whether literally or figuratively? Hypnosis deceives the subject and creates a simulated, temporary reality. Did prog attempt to simulate an alternate reality, or did it, on the other hand, try to describe and comment on our actually-existing reality (and to point towards possible paths beyond it)? An easy way to figure this out is to equate sonic effects, whether “intense” (backwards masking, echo, etc.) or “modified” (like fuzzed guitar) with the deceptive hypnotic gesture.

Using this as a metric, the bands of the Vertigo pantheon may be classified as representing either HYPNOTIC (simulating reality) or ANTI-HYPNOTIC (discussing and/or confronting reality) prog tendencies, as follows:

1. Cressida (August 1970) anti-hypno. Short, often poppy songs, clear singing that is “free from mannerisms” (sayeth vertigoswirl.com). Lyrics frequently about love and even when “trippy” are often insightful and rooted in realism (as with “look to this marble mirror/you can’t believe it when/they say you’ve aged a decade in your last few years”) and music that avoids muddy excess at almost every turn.

2. Fairfield Parlour (August 1970) anti-hypno. Soaring harmonies, tragipop outlook and an obsessive approach to lyric writing that entails contrasting mundane details about daily life with yearning everyman choruses. There’s an intense Village Green-era Kinks glorifying of the past that is arguably its own kind of alternate reality-spinning, but as with the Kinks, these paeans are so laden with the particulars of everyday life that they remain powerfully tethered to concrete social reality, and use those elements instead to construct an argument about how to navigate this failing world and resist its mechanized/algorithmic orders.

3. Gentle Giant hypno/anti-hypno. Rian Murphy says “They have a Yes-like quality that involves repeating, modulating, spiraling figures. Often they have vocal arrangements sung in rounds based in Brit-folk madrigals.” These guys’ lyrics are often abstract enough that it is hard to pin down which side of the hypno-fence they lie on, but the words tend to sit in album-long narratives that are seriously anti-hypno. For example, The Power and the Glory (September 1974) is all about a seething politician’s ruthless ascent, maybe the closest a prog album concept ever got to paralleling the evening news (unless you count Megadeth-style metal or Pedro the Lion’s Winners Never Quit as prog). “Cogs in Cogs” — one way to describe the industrial spiral form — in particular suggests the viciously ouroboric oscillation of capitalist subjectivities, both lyrically and through the jams, without ever clearly explaining itself.

Check penguindf12 and epignosis’s analysis and you’ll see what I mean: “Cogs in Cogs is an intricately arranged rocker, with many weird tempo changes, and the middle section “The circle turns around, the changing course is calling” is dizzying. This a capella section is a two-part vocal harmony cycle, with one vocal in 6/8 and the other in 15/8, musically depicting cogs in cogs … “Cogs in Cogs” Despite the leader’s efforts, he confesses that his empty promises have not paved the way, and now the cogs of discontent are turning. The music is fast paced and frantic, reflecting the mounting panic of the person in charge.”

One could argue that the words’ abstract, generalized quality makes them politically useful by allowing them to apply in different eras of political conflict. But ultimately, the lyrics’ non-specificity is just a refusal to commit, like those of prog giant Jon Anderson (there is no negation in Yes). The lyrics are positioned close to the (whimsical) edge of the normally realistic anti-hypno side of the spectrum.

4. Jade Warrior hypno/antihypno. Like Gentle Giant, Jade Warrior contains aspects of both hypnotic and anti-hypnotic prog. This band was maybe the first major (?) rock player to incorporate African, Latin American, and Asian sounds, not just as window dressing, but actually into core parts of songwriting. This “world” orientation creates amazing sonic effects over the course of their first three records, especially the flutes which immediately signify “feudal Japan.” And on the first record the lack of rock drumming heightens the floaty, gossamer vibe. These effects create a powerful illusion of being transported to another realm, which in this case is just another part of the physical cultural world organized, globalized, and dominated by capital.

But there are ways the proto-world music approach achieves an opposite effect on the listener, something akin to Brecht’s alienation effect, calling attention to the falseness of a play through strategies used as a “means of breaking the magic spell, of jerking the spectator out of his torpor and making him use his critical sense.” Because the inclusion of these instruments was so unusual at the time, it could have startled listeners and piqued them cognitively, “popping” them out of the bubble of the rock audio experience into thinking about the band, their methods, and historical contexts. It’s ironic that the psychedelic/pro-gressive style of rock, whose vocabulary they were expanding, was already incapable of engendering that cognitive “pop,” or, as in Duchamp, the logical moment. Only five years before the release of the first Jade Warrior album, the first psych albums were landing and forcing the heads to think harder, not softer, about “reality.”

Like the effects achieved by their exotic instruments, Jade Warrior’s lyrics also straddle a weird line between blissed-out and socially-aware, so on the one hand we get delicious imagistic drivel like this, from “The Traveller,” the first album’s opening track:

Across the desert in a ship of sparkling silver went the man / With scarlet poems on the sails he played and softly sang / His name was freedom when he lived / Forgotten when he died

But elsewhere we find stark and realistic assessments of modern problems, like the King Crimson-y observations in “A Prenormal Day in Brighton” (Paranoic problems hurting my head) and “Snakebite” (Cyanide sunrise/Communist war cries/Government gum-rise). But even more blatantly anti-hypno are this set of direct instructions to the listener, from “The Demon Trucker”:

Climb up on the stairs and stomp around the bedroom / Open up the window get yourself some headroom / Turn up all the volume wake up every mother

And, similarly, from “We Have Reason To Believe,” an account of a (presumably real) bust at one of their gigs:

Cos they were sniffing and a snuffing and a moralizing too / We only got together just to have a good time / And here they were implying we’d committed a crime / I tried to tell ‘em that we weren’t doing no wrong

In both of these songs, the tone is heavier or sharper, even punk in its attitude. The message is not one of surrender to the fantastic spell of another reality, but rather of observation, analysis, and defiance of the status quo: the disenchantment of the domination of modern life and an uprising against its logic. But there can only be one band that definitively straddles the hypno/anti-hypno divide while striding god-like at the outermost and heaviest ring in the Vertigo orbit.

Spiral Architect

“Spiral Architect” is the last song on the fourth album by Black Sabbath, Sabbath Bloody Sabbath, released by Vertigo in Europe and South America (1973). This album is a crucial late integer in the classic Black Sabbath sequence. The song “Spiral Architect” is framed, portentously and perhaps ironically, by classical guitar at the beginning and canned applause sounds at the end. And then, as the applause fades out, the music returns: jazzy, meandering, and nonchalant: an end that is not an end, signifying the infinite time of the phonograph record. This formal frame, obviously pasted on the edges of the song itself, signals to us that something both important and contradictory will take shape within.

The lyrics of “Spiral Architect” were written, as all Sabbath songs from this period, by bassist Geezer Butler. The song describes a magical lifeworld that is also a spiritual nightmare. It is an eerily double world: magical and yet utterly synchronized; always already mediated as a representation and yet viscerally real. It is filled with warmth and order but at the same time with sadness and death. Contradictions ornament and animate this spectacular celluloid earth: snow is black, fathers cry, sanity separates.

The “architect” of this world — is it God, is it Satan, is it the recording engineer, is it Olav Wyper? — watches his children grow, under “spiral skies” (a figure that at once evokes both cosmic depth and the flatness of the lateral horizon), but he is also their “undertaker.” He is the sovereign: he decides who lives and dies. And yet this world designed and adjudicated by the sovereign is warm and it is good, or at least that’s what the narrator is trying to convince us (or himself) of in repeating an increasingly anxious-sounding chorus.

The song concludes:

Watching eyes of celluloid tell you how to live / Metaphoric motor-replay, give, give, give! / Laughter kissing love is showing me the way / Spiral city architect, I build, you pay

In the devastating apposition of the final verse, as the spiral architect builds its brilliant, mechanized, and spectacular world, the addressed subject of the song — you — must pay. This magical world is not free. Its godlike construction turns out to depend upon a contract that compels our payment. We are the world’s denizens, and we must pay money, as a form of cosmic rent, to the spiral architect, landlord of this world. The utterly brilliant final twist is that the fundamentally coercive logic of money is exactly the thing that binds us to the sidereal spirals of our seemingly magical world.

Ozzy sings the refrain: I know that it is good. Does he, as the song’s narrator, actually believe this? Is this an example of irony? Could we say that Sabbath is ever ironic? The spiral architect is “the Lord of this World,” recalling the cut from Master of Reality: “your world was made for you by someone above.” This is the unique heavy power of ambivalence in the message of Black Sabbath: the warmth and beauty of the world is simultaneously rendered — sometimes coldly, sometimes hysterically — as the domination of a shadowy but brilliant figure who subsists within the very phenomenal structure of the world he organizes, while appearing from above. The streetwise social stakes of this ambivalence can be sometimes difficult to grasp. For comparison, and as a thought experiment, listen to the incisive irony and social realism of “It’s Only Money” by Thin Lizzy, from the equally but differently darkly brilliant Night Life, coincidentally (?) released on Vertigo, less than a year after “Spiral Architect.” Thin Lizzy and Black Sabbath are both notable in the history of 70s rock for being self-consciously, in their own imagination as well as that of their label’s marketing department, urban working-class subjects embattled in class struggle (“They’re from Birmingham England. It’s a rough town. Their first album shows it — Tough, Stark, Uncompromising Rock, And Already No. Six in England”). Phil Lynott’s lyrics directly exhibit this proletarian position by calling out the only figure of speech that actually makes sense, but this time in a brutal refusal of metaphor that precisely and powerfully reveals its fundamental fiction: money.

You don’t believe in love / You don’t believe in hatred / Put your money in the bank / It’s the only way to save it / You try to make a buck / But you haven’t made a penny / You need a little luck / But you know you won’t get any / Oh money, its only money, / Its only money. / You don’t believe in God / You don’t believe in glory / You’ve got a brother in the clinic / Tells the same kind of story / If he had another life / He’d know what would be waiting / If he had another soul / He could sell it all to Satan / You don’t believe in war /You don’t believe in Jesus / Got a sister in New York / She knows how she pleases / Walking the streets / On the south side of the city / Trying to make ends meet / Isn’t that a pity … for money / Money, money!

The Spiral of Capitalism

Ok let’s play everybody’s favorite fun game and take a step back, like Bob Weir says (who has something elsewhere to say about spirals). Let’s take a step back in terms of the spiral concept: like a DJ let’s move the record back and make a spiral scratch. Let’s make the commodity talk; let’s talk about commodities. Records are spirals. Records are things we buy. The things we buy and sell (“commodities”) are the fundamental units of capitalism. Capitalism organizes the world through the exchange of commodities, as Karl Marx, among others, has pointed out. There are many compelling ways to describe this organization of the world through the exchange of commodities. We will return to the particular sense of the spiral commodity (i.e. the phonograph record) in a minute but for now the point we would like to draw is that capitalism itself is the fundamental spiral.

Marx describes capital as a process of ever-expanding value that has the form of a spiral. This process is succinctly expressed by Marx in the formula: money → commodities → (more) money; or, more succinctly: M — C — M’. The capitalist exchanges money for commodities, which are in turn exchanged for more money, which is then exchanged for more commodities, which can then be exchanged for yet more money, and so on and on — until the break of dawn, which is to say: the absolute and final break, the break that is unfolding and the rift in which we find ourselves (according to the French ultra-left group Theorie Communiste) between the impossibility of the affirmation of the proletariat without affirming capital and the impossibility of negating capital without negating the proletariat; stuck in the middle of the split with you, impossible comrade. Or until the break of dawn that in the spiral of capitalization is another sort of rift, the so-called metabolic rift, between human production and the natural world which it continually expropriates and which it is finally exhausting before our smoke-filled eyes.

But until this break of dawn, while M — C — M’ is still the (insane) formula for capital accumulation, for the rest of us suckers, we just sell our own commodities (and as proletarians separated from the means of production, all we actually have to sell is our own labor power, in the form of the wage), in order to pay the rent or buy some food or buy a record (C — M — C), and thus to reproduce ourselves as living music-loving labor for more exploitation by capital. Cool spiral.

In Marx’s analysis, capital valorization is a process in continuous and unending motion, driven to constantly accumulate value as it breaks down further and farther limits to its own expansion, and swallows more and other forms of life in order to cycle ever forward, triggering violent crises which it always resolves in its own favor with austerity and debt, and it goes on and on until the world ends like we just said, or we get communism. This capitalist death spiral is the evil twin or the secret meaning or the raw social content of the sense of formal progression towards freedome in modern jazz. We’ll say more about this at the end.

Besides the phonograph record, the commodity that most obviously has the form of a spiral is the slinky. A slinky is a helical spring toy invented in the early 1940s, just as recorded music was consolidating its LP spiral commodity form. A slinky performs the trick of appearing autonomous, it can travel down a flight of steps “as it stretches and re-forms itself with the aid of gravity and its own momentum, or appears to levitate for a period of time after it has been dropped.” It also slinks, as befits the bearer of the mysterious and horrible secret of commodity fetishism: “the commodity reflects the social characteristics of men’s own labor as objective characteristics of the products of labor themselves.” The capitalist commodity seems to spin in its own orbit, as Adorno evocatively puts it, and the slinky embodies this fetish in an enduring and charming way.

A conflation of these two forms (phonograph and slinky) actually arrives in October 1959 (a mere four months before Giant Steps) when Link Wray records his third single, entitled “Slinky.” Why would he call this instrumental song “Slinky”? His name is symmetrically encased in the word sLINKy; could it have been a nickname? It makes linguistic sense.

Here are a couple of significant points about this recording. First, it demonstrates Link Wray’s crucial contribution to the development of the electric guitar as a medium of explosive distortion. This effect became associated forever with leather-jacketed, switch-bladed rebellion in Wray’s first single, “Rumble” — the title in fact is simultaneously a gang fight (class war without class consciousness) and a sound effect. Distortion is the introduction of noise into the sonic palette of guitar sounds. It is the rejection of society’s prohibition of noise and its need to control “bad” sounds. Jacques Attali wrote in 1977 that “Everywhere power, expressed in centralized legal apparatuses, reduced the noise made by others and adds sound prevention to its arsenal,” pointing to statutes regulating after-hours parties and automobile horns as early examples. So Wray’s distortion doesn’t just amplify the rebellion inherent in his songs, it is itself a rebellion.

But by the time of the third single it might seem that Wray is no longer rebelling in quite the same explicit way. “Slinky” is essentially a muted retelling of the rumble, the distortion is slicker, more restrained, so while the song is great, it’s not so rad. It’s obviously become another rock commodity formula (for the moment at least.)

These novelty noise tunes and sneaking toys and the phonograph record and capitalism itself share the same basic spiral form. But this spiral structure of capital (and everything else) is not simply a set of expanding concentric circles; the spiral is formed by a reflexive motion that always doubles back upon itself as it acquires greater territory and velocity in time and space. Soren Mau lucidly recapitulates the reflexivity in Marx’s thought-image of the spiral form of capital:

Capital sustains itself by means of its constant change of form and its continuous movement through the spheres of circulation and production. With capital, the entry of money into the sphere of circulation — that is, the act of buying, or giving up the money for a commodity — is merely ‘a moment of its staying-with-itself’; it stays with itself by renouncing itself. By performing this deeply tautological movement, capital constantly re-establishes the conditions of its own repetition: it contains what Marx calls ‘the principle of self-renewal’, or, in Hegelian terms, it ‘posits’ its own presuppositions. By transforming the circulation of commodities and money into this spiral-like form, capital transforms the “bad infinite process” of simple circulation (C — M — C) into a self-referential infinity. As a social form, capital is completely indifferent to its content; the only thing that counts is whether or not value can be valorised. For this reason, the self-relating movement of capital is truly a self-relating negativity: it negates any particular content by transforming it into real abstractions in order to absorb it into the vortex of value.

In this spiral of infinite valorization, capital posits its own presuppositions every time it loops back. It continually re-establishes the conditions of its own repetition. This is why it is so hard to resist, and this is the reason for what Mau calls the mute compulsion of capital. “Capitalist production is the production of capitalism.” This is the tautological formula of the domination of capital. The spiral of its self-referential reproduction drills down into every minute recess of our social life. Another way to say this is that as capitalism produces commodities and circulates them and thereby produces surplus value, it also reproduces the capital relation itself (to labor and to nature) — on an increasing scale. In the spiral movement of capital, those things which were originally the preconditions for its existence, become the result (ie are “posited”) of its existence. So in the course of capitalist production, while piles of objects and stacks of records and gallons of poisonous chemicals in the air and soil accumulate, it is not only these commodities and their waste but also the capitalist relation of production itself (a relation of coercion and domination) which is reproduced, in larger and more intensive scales.

We might say the spiral of capital is the basic fluid diagram that animates all the spirals that pop up like symptoms, like a hypnotic freckle on the skin of our sensible commodity world, including record covers and musical forms. Okay on to rap.

Sugar Hill

The ebullient, frenetic logo of Sugar Hill (est. Engelwood, NJ, 1979), employing multiple spirals, loops and near-spirals across the candy-colored cursive rendering of the label name, presents rap as a jubilant, city-based phenomenon. The alternating purple-red-orange-yellow sections that make up the “path” of the calligraphy evoke the squares on the game Candy Land (1948), and enlarge the message of the logo into something utopian and exclusively youthful. And since the sections end at the silhouette of a city (which, though composed of generic skyscrapers, reads as New York), the logo suggests the reimagining of Oz and its colorful road in the musical The Wiz (1974), combining the idea of the party with a wondrous fantasy land Shangri-La. This party quality is echoed in the crowd noises in the background of so many early Sugar Hill tracks, like Positive Force’s “We Got the Funk,” “Rapper’s Delight” by Sugar Hill Gang and, most explicitly, Grandmaster Flash’s “The Birthday Party.” And unlike the sterile applause at the end of Sabbath’s “Spiral Architect,” these sound effects are integrated seamlessly into the songs’ groove. The logo tells the consumer that if you want your party to go beyond just having fun, and to in fact link to every other party on the block-borough-city-globe, through a delicious candy-colored sonic network, you will buy this record.

That record, especially in the initial era (‘79–‘84ish) of Sugar Hill (and of rap as a genre), was likely to be a 12” with two long songs instead of a full-length album. The convention for 12” singles is to have no art on the sleeve, since they are often going to “consumers” within the industry like DJs and radio stations, who are actually “producers” in their own spheres, and so don’t require an “ad” on the cover to “sell” the music. There’s also the economic necessity — these singles are to be hustled into as many clubs and shops and blocks as possible, so the added expense of sleeve art that is specific to each recording becomes infeasible.

The 12” cardboard sleeve is die-cut to reveal the circular label. Sometimes on a 12” the label is the only place where song and band information can be found. Sugar Hill used a basic template for all their 12” releases that was colored blue, with the label name and logo on the top, which could be reused for any single. This larger version of the logo ends in an enormous spiral stretching from the final l in Hill to the center die-cut. In addition to the flamboyant flourish it adds to the lettering, this megaspiral does two things: it repeats the sleeve’s spiral inside the label, and it guides us visually from the name of Sugar Hill to the name of the song and rapper located on the center circle, privileging the collective label entity above the individual musician and suggesting that any music produced by Sugar Hill will adhere to the utopian, youthful, and urban parameters affirmed in the logo.

The larger version of the logo has elements that go beyond flat spiraling to imply three-dimensionality: the letters are rendered in a puffy tubular way that suggests snakes or straws (Pixy Stix?). Also, the fact that the sleeve logo maps to and then ends at the inner logo (which we can see because of the die-cut) raises an interesting 3D possibility, that by following the cover spiral we are traveling — maybe we are tunneling underground because this spiral is so tubelike — from the outside of the record to the inside of the record. And what do we find at the end of the tunnel? The smaller logo, mirroring the larger one to achieve an infinite regress as they stare at each other, the package containing and sustaining both iterations.

A 3D spiral, or more precisely, a 2D representation clearly meant to suggest the objects in 3D perspectival space. This is a type of spiral with which we are familiar, but it’s typologically different than Atlantic or Vertigo. But how do we describe the way a line travels to create a spiral shape, whether in two or three dimensions? You just keep drawing circles but at each revolution the line is pulled farther into space (depth). You keep drawing a circle but the protractor or whatever device you’re drawing with keeps getting narrower or wider. In other words the length and width are constantly contracting or expanding. Length, width, and what we could call contraction/expansion are the three axes, or the three forces that act on the line as it travels to create the spiral form. What are the three forces that acted upon Sugar Hill?

The first force could be the corrupt business practices of the label owners Sylvia and Joe Robinson, underpaying their artists and engineering a kind of underground monopoly on the initial rap scene. Beyond the historical specifics of Sugar Hill, this ties to the larger tradition of exploitation of Black artists by white businessmen. This force, of capitalist domination, conflicts with a second one, the utopian freedom and positivity characteristic of the artists and music on the label, and in fact of most pre-Run-D.M.C. (“New School”) era rap. You can hear this tension between the lines of Sugar Hill Gang’s “Rapper’s Reprise (Jam-Jam)” when Master Gee, in a brilliant ironic reversal, says “The rap I have controls your will/Which is typical of Sugarhill.” The pure subversive libidinal delight, in these lines, of turning the tables and celebrating in party form the formula of capital’s domination of labor, is utterly contagious. The easygoing, generous spirit in which this statement is made is really amazing, not to mention the hilarious academic cadence of “which is typical of Sugahill.”

We could say it is the tension between these two forces, of freedom and domination, that makes the line curve. But what also makes the curve into a spiral is the exploding audience and in fact the insanely rapid social evolution of rap as a musical commodity form.

But calling rap’s development an “evolution” is misleading. It suggests a smoothness and inevitability that overlooks the repetitions, missteps, ruptures, and doublebacks in its history, as well as the influence of random chance as a factor. Part of Marxist dialectical materialism is the critique of this continuous and progressive idea of history, which is a bourgeois idea. For Marx, history itself is a spiral and one day we will spiral right out of capitalism, hopefully into communism but maybe into something even worse (if we haven’t already.) Lenin distinguishes this idea of history as a dialectical spiral from the incremental idea of development that is conventionally understood as “evolution.” In 1915 Lenin writes:

In our times, the idea of development, of evolution, has almost completely penetrated social consciousness, only in other ways, and not through Hegelian philosophy. Still, this idea, as formulated by Marx and Engels on the basis of Hegel’s philosophy, is far more comprehensive and far richer in content than the current idea of evolution is. A development that repeats, as it were, stages that have already been passed, but repeats them in a different way, on a higher basis (“the negation of the negation”), a development, so to speak, that proceeds in spirals, not in a straight line; a development by leaps, catastrophes, and revolutions; “breaks in continuity”; the transformation of quantity into quality; inner impulses towards development, imparted by the contradiction and conflict of the various forces and tendencies acting on a given body, or within a given phenomenon, or within a given society; the interdependence and the closest and indissoluble connection between all aspects of any phenomenon (history constantly revealing ever new aspects), a connection that provides a uniform, and universal process of motion, one that follows definite laws — these are some of the features of dialectics as a doctrine of development that is richer than the conventional one.

Damn, Lenin could write! Sugar Hill rap’s expression of those “inner impulses towards development” as an on-and-on forever-ness is like James Brown’s muscular vocalized insistence on overcoming his own limitations to persevere. Richard Meltzer characterized Brown as the “paradigm of completeness,” supported by Eva Dolin’s concert review in which she says “[Brown’s] ardent fans are amazed when, instead of a finale, the pace quickens and the James Brown talent explosion continues on and on.” And, as Meltzer points out, when Brown says the phrase “one more time” one million times, we are actually encountering a “continuation to infinity.” This impulse towards infinity, in James Brown and in rap, tries to square the circle of the bad infinity of capitalist circulation, and points the way out of its rifts, towards the communist horizon of infinite human creativity.

“Rapper’s Delight” (Sugarhill Gang, 1979, cat. #SH-101, the first rap single) perfectly embodies the logo’s utopian party spirit as well as its sprawling spiral structure. The three MCs — Wonder Mike, Big Bank Hank, and Master Gee — hand the mic off between them in a circle, over and over nine times in the course of the song’s 15 minutes while the lyrics accrue through ten giant verses, creating a corkscrew of words.

The track opens with Wonder Mike welcoming all races to, getting surreal at the end to make clear the party is infinite, “A to the black, to the white, the red and the brown, the purple and yellow.” Echoing JB, each of Master Gee’s verses explains,

Well it’s on and on and on, on and on / The beat don’t stop until the break of dawn

Black Jazz Spiral

We began this essay by thinking through the spirals of Atlantic Records and Coltrane’s Giant Steps and we return to consider the unprecedented overflowing of creativity and production as jazz modernized after bop beginning around 1960. The unquenchable obsession of Coltrane, Coleman, Taylor, Shepp, Ayler, et al with progress, with new forms and directions — the next step forward — not in order to rest at a final endpoint, but instead as urgent ends in themselves transformed what had up until that point been a linear historical evolution of forms into a furious dialectical spiral. The emotional forms and the technical and theoretical discoveries newly made in this period were immense. These players/composers were producing so fast and in such cross-fertilized collective conditions, that there was effectively no time for consolidation of new insights. More precisely, the reflection and organization that normally occurs in artistic development between album releases, in this case was happening so fast that it oftent occurred within an actual performance. With obsessive production of forward movement in black jazz there is no consolidation point. Like the circular breathing of Rashaan Roland Kirk and Roscoe Mitchell where in-and-out breaths are conjoined and solos are extended almost infinitely, in the modern jazz era we’re talking about, thought and action become one. The division of labor between composition and performance, between the “mental” domain of writing and “manual” domain of playing, collapses in this period of accelerated production. The production of jazz becomes an intensified/purified assembly line with no breaks and no management and with music continually flowing through the conveyor belt and practically destroying the very factory from which it issues.

This barrier-breaking quantity and quality of production is also evident in improvised jazz’s (non)relation to notation. Notation is secondary in most of these cases because the music wasn’t composed by writing. Notation merely captures part of it, after the fact. And it can’t even do that. It’s like when Coltrane, having been shown a transcription of his solo on “Chasin the Trane,” was unable to sight-read what he’d improvised. Ekkehard Jost breaks down this relation, and the fundamental displacement of notation by the vinyl record itself (which Adorno had earlier noted) in his book Free Jazz (1974), in case you need (for some weird reason) the Latin translations: “In traditional occidental art music (discounting the exceptions) the composer’s ‘imaginatio’ first emerges in the res facta of the notation and only then is realized in sound by the ‘interpretatio,’ while imaginatio and intepretatio coincide as a rule in jazz, at least in improvisation. Thus a graphic record in the form of notation is replaced by a phonographic on disc or tape. Transcription of it serves only to help the ‘memoria’ in analysing structure or style.”

The utopian trajectory of the spiral — imagined, theorized, and produced by Black Art/Jazz in the period that roughly commences with Giant Steps — and the concomitant collapse of imagination and interpretation (thought and action; sign and meaning; etc and etc) is the thing we want to identify in this history and, indeed, to mobilize again in our own publishing efforts. The sense, at the time, that each successive integer in the jazz sequence is one step further along an experimental line that must become increasingly free is an absolutely thrilling idea. Indeed it is the very form of emancipation and is absolutely political in its aesthetic implications and social effects.

The titles of avant garde jazz records from this period bear out these ideas of obsessive forward movement: The Way Ahead. Point of Departure. The Shape of Jazz to Come. Giant Steps. One Step Beyond. Miles Ahead. What is always moving forward in this black jazz sequence? How far did it go? When did it end? Why? This is a fascinating and complex question, and one to which we return in a future publication. For now we can enumerate a few of the contradictory endings to the black jazz spiral sequence: r & b forms infused with explicitly political lyrics (Albert Ayler’s New Grass, Archie Shepp’s Attica Blues), ECM’s quasi-mystical new-age-yfing of free jazz’s radical spiritual orientation, the black/white fusion of Weather Report, Don Cherry’s adventures into world music, or even Wayne Shorter’s solo in “Aja.” We love all these records but there is something in them that signals a defeat.

Today it is uncommon, outside of certain insignificant techno circles, in music as well as in general attitudes and sentiments, to suggest that a spiral is upward or positive or progressive. We are regularly confronted nowadays, in pop/dance music and in life itself, with spirals, but they are always “downward spirals” — spirals that the Cambridge dictionary defines as “a situation that gets worse and is difficult to control because one bad event causes another.” When we say, in everyday metaphorical speech, that something is spiraling, we mean it is spinning out of control toward destruction, not that it is moving towards communism. Like the wage-price spiral. Or Nine Inch Nails. When the black jazz spiral ends, we are left with what Jacques Attali called the society of repetition: “Fetishized as a commodity, music is illustrative of the evolution of our entire society: deritualize a social form, repress an activity of the body, specialize its practice, sell it as a spectacle, generalize its consumption, then see to it that it is stockpiled until it loses its meaning. Today, music heralds — regardless of what the property mode of capital will be — the establishment of a society of repetition in which nothing will happen anymore.” The end of the black jazz spiral heralds the postmodern era in which every new style is simply an invocation or reference of a previous one. We get returns, reissues, citations, and influences but nothing new. Today we inhabit this world of diminished forms and the suspension of that emancipatory horizon that harbored the very idea of revolution.